Sharp-shinned Hawks at Risk

Sharp-shinned Hawk Image by Bill Moses

Sharp-shinned Hawk

(Accipiter striatus)

Although Sharp-shinned Hawks are one of the most numerous species counted during migration at many watch sites, many of the trends recorded over the last ten years show a decline that warrants a closer look. Of all species of North American raptors, more sites showed declining Sharp-shinned Hawks during the last decade than any other species, with 47.4% of 76 sites continent-wide showing declines from 2009-2019. Over the last twenty years, Sharp-shinned Hawk counts have declined at almost 50% of count sites, ranking it as the most declined species of the of the 27 migratory raptor species counted at sites across North America. CBC trends indicate winter declines of wintering Sharp-shinned Hawks in the East region and portions of the Central region, suggesting that short-stopping is not the reason for the declines at migration count sites. The declining trends likely represent actual population decline. Research is needed to better understand migration ecology and regional conservation threats for this species.

Global Conservation Status:

IUCN 10/01/2016 – Least Concern (LC)

U.S. and Canada Conservation Status: Listed as endangered in Puerto Rico. Critically imperiled in 7/66 states and provinces (DE, IL, KS, LA, MS, NC). Imperiled in 8/66 states and provinces (SK, CT, IN, MA, MD, MO, ME, TX). Vulnerable in 22/66 states and provinces. Apparently secure in 32/66 states and provinces. Secure in 7/65 states and provinces.

Sharp-shinned Hawk Population Status by State and Province in the US and Canada

The data used in this figure are listed above. These data were compiled from NatureServe and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Birds of Conservation Concern List:

Subspecies resident in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands is listed on the United States Fish and Wildlife Service Endangered Species Act (as of January 15, 2021).

Range:

From Alaska to Northern Argentina. Also inhabits the Caribbean Islands.

Habitat:

Nests and winters in forested habitat with a preference for mixed coniferous-deciduous forests. Will use suburban habitat during wintering, likely hunting at bird feeders.

When Did Sharp-shinned Hawk Migration Counts Begin Declining?

Sharp-shinned Hawks are rarely seen during the breeding season and are considered highly difficult to census during nesting. Along with many other raptor species, Sharp-shinned Hawk migration counts dropped due to the use of DDT during the 1940s through 1960s (Bednarz et al, 1990). Following the DDT ban, Sharp-shinned Hawk migration counts rebounded more rapidly than any other raptor species. Sharp-shinned Hawk migration counts started declining again in the late 1980s and early 1990s, starting at coastal sites and then inland. Some analyses showed elevated blood parasite loads and organophosphates in migrating Sharp-shinned Hawks (Powers et al, 1994). In the 2000s, analyses suggested migration counts could be declining due to an increase in short-stopping as higher wintering counts in Northeastern states were documented. In the past decade, Christmas Bird Count data for Western and Midwestern North America show increases in wintering Sharp-shinned Hawks, possibly also documenting short-stopping behavior. In the Eastern United States, however, recent declines in winter have occurred, reinforcing the declining population suggested by data from the watch sites.

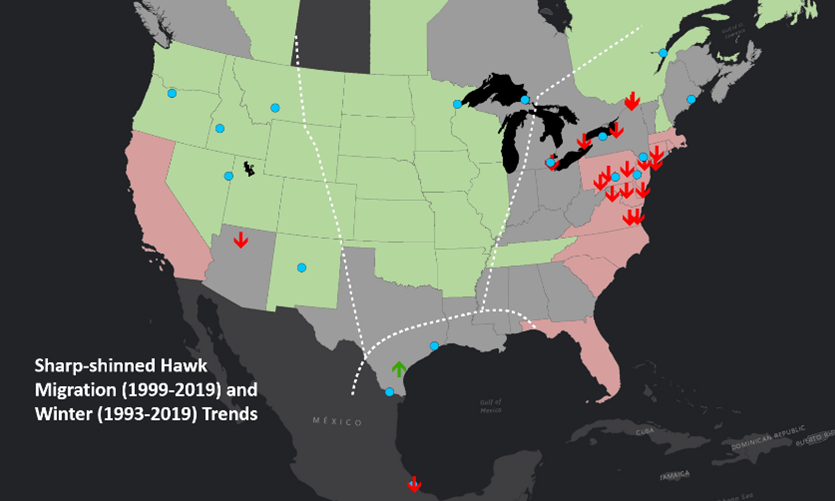

RPI Trend Maps:

These maps summarize the latest RPI trend analyses for count sites throughout North America.

Figure 2. Summary map of RPI and CBC trends from 2009 to 2019 for Sharp-shinned Hawks.

Figure 3. Summary map of RPI and CBC trends from 1993 to 2019 for Sharp-shinned Hawks.

Find the interactive version of the Christmas Bird Count (CBC) maps here.

BBS: Inadequate data

Why are Sharp-shinned Hawk Migration Counts Declining?

Some possible reasons for Sharp-shinned Hawk population declines include loss of forest habitat in the boreal region, loss of prey species, environmental contaminants, and infectious disease. The increase in Christmas Bird Count numbers in the West suggest migratory short-stopping is possibly occurring, which involves individuals not migrating as far south, or a decrease in the proportion of individuals in populations that migrate at all. Short-stopping events are likely linked to a combination of warmer temperatures and increased food resources. However, short-stopping does not explain the declines observed in both the CBC and migration counts in the East region. West Nile virus has increased in Canada and the northeastern United States. Sharp-shinned Hawks are vulnerable to the virus, which can result in mortality (Saito et al, 2007). Declines in songbird prey and increased use of chemicals in northern forests also could play a role (Gray 2013). Recent increases in wildfire frequency and intensity also may impact Western populations.

Threats

Loss of Habitat

Sharp-shinned Hawks prefer forested habitats with mixed conifer composition. The species depends on large tracts of contiguous forest for breeding. Evidence also suggests a preference for younger, mixed coniferous forests for hunting as well as breeding in the Midwest and Western regions of North America. Sharp-shinned Hawks can overwinter in a variety of habitats including urban and suburban developed areas (Bildstein et al. 2000). In northeastern forest habitat, Sharp-shinned Hawks may also be affected by the cycling of the eastern spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana), a native species of moth that defoliates spruce trees. The widespread practice of aerial spraying for spruce budworm to protect the forest for future logging has been observed to coincide with the decrease of some songbird populations such as evening grosbeaks, which are known spruce budworm specialists. Spruce budworm outbreak severity and length are expected to increase with predicted climate increases in the next 20 years (Gray 2013). More research is needed to explore these relationships. Studies have shown that over 1.6 million acres of boreal forest has been lost due to logging in the last three decades, which could also affect nesting birds (Wildlands League 2019). The impact of the overall increase in both number of wildfires and fire severity in Western North America on raptor populations requires further investigation. These changes can result in profound changes in the ecosystem, including vegetation shifts, invasive species, a decrease in biodiversity, and population shifts. Some preliminary research has shown raptors may not use nesting habitat after a fire, which suggests raptors have experienced further declines in usable habitat due to increased fires in the West (Gao, 2020).

Loss of Prey Species

Sharp-shinned Hawks are a highly specialized predator of birds, primarily passerines, which constitute 90% of their diet. Sharp-shinned Hawks prefer hunting in forested areas but also will hunt at suburban bird feeders, particularly in winter (Bildstein et al. 2000). The most steeply declining species within temperate forests are birds. In fact, populations of birds have plummeted in the last 50 years, dropping by nearly three billion across North America (Rosenberg et al., 2019). As mentioned above, the common practice of spraying for spruce budworm outbreaks in the Canadian boreal forests may serve to further reduce songbird populations. More research is needed to examine if songbird predators, including the Sharp-shinned Hawk, are affected by the drop in prey abundance.

Environmental Contaminants

Although the use of organochlorines in North America have become heavily regulated, the effects of other agrochemicals including pesticides and herbicides on Sharp-shinned Hawks have not been satisfactorily explored. The use of organophosphate insecticides to control spruce budworm outbreaks in the Canadian forests during the early 2000s was speculated to be a culprit for the early declines (Viverette et al, 1996) and could be contributing to current trends as well. Noenicitinoid pesticides have also been used in forests to control hemlock wooly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) and other forest pests as well as suburban yards. As an avian predator, Sharp-shinned Hawks are susceptible to bio-magnification of contaminants such as pesticides ingested by their prey. Because many of their songbird prey migrate out of the United States in winter, Sharp-shinned Hawks could be exposed to DDT and other chemicals still being used in Central and South America.

Infectious Disease

West Nile virus (WNV) first reached the United States in New York in 1999 and has since spread across the continent, including Canadian boreal forests. The primary vectors for WNV are mosquito species Culex restuans and Culex pipiens, and many avian species serve as reservoirs. Sharp-shinned Hawks infected with the virus present neurologic symptoms and often die. In 2002, 40% of the deceased Sharp-shinned Hawks submitted to the National Wildlife Health Center were positive for WNV (Saito et al, 2007). The timing of the decline in Sharp-shinned Hawks is consistent with the West Nile virus mosquito vector index in Pennsylvania, suggesting trends in the northeastern US might be related to WNV prevalence in the region (Bolgiano 2019). Sharp-shinned Hawks are infected with WNV through a mosquito bite or through feeding on infected birds (Vidaña et al, 2020). Sharp-shinned Hawks may be more frequently exposed to the virus than other raptor species due to their specialized consumption of common WNV reservoir species. More research is needed to determine the extent to which WNV has impacted raptor populations, including Sharp-shinned Hawks.

Written by Rebekah Smith

Literature Cited

Bednarz, J. C., D. Klem Jr., L. J. Goodrich, and S. E. Senner. (1990). Migration Counts Of Raptors At Hawk Mountain, Pennsylvania, As Indicators Of Population Trends, 1934-1986. The Auk, 107, 96–107.

Bolgiano, N. (2019). Evidence for West Nile Virus-Related Avian Declines in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Birds, 33(1), 2-11.

Bolgiano, N. (1997). Pennsylvania CBC counts of Sharp-shinned and Cooper’s Hawks. Pennsylvania Birds, 11(3), 134-137.

Boreal Logging Scars, Wildlands League. 2019. Executive Summary. https://wildlandsleague.org/media/LOGGING-SCARS-FINAL-Dec2019-Exec-Summary.pdf

Keith L. Bildstein, Kenneth D. Meyer, Clayton M. White, Jeffrey S. Marks, and Guy M. Kirwan, Birds of the World Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated January 1, 2000

Bildstein, K. L., and K. Meyer. (2000). Sharp-shinned Hawk (Accipiter striatus). In The Birds of North America, No. 482 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA

Farmer, C. J., & D. J. Hussell. (2008). The raptor population index in practice. State of North America’s birds of prey. Series in Ornithology, (3), 165-178.

Farmer, C. J., and J. P. Smith. (2010). Seasonal differences in migration counts of raptors: Utility of spring counts for Population Monitoring. Journal of Raptor Research, 44(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.3356/jrr-09-31.1

Fink, D., T. Auer, A. Johnston, M. Strimas-Mackey, O. Robinson, S. Ligocki, W. Hochachka, L. Jaromczyk, C. Wood, I. Davies, M. Iliff, and L. Seitz. (2021). eBird Status and Trends, Data Version: 2020; Released: 2021. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. https://doi.org/10.2173/ebirdst.2020

Gao, J. (2020). (master’s thesis). Effects of Woolsey Fire on Nesting Territories of Southern California Red-Tailed Hawks (Buteo jamaicensis). Oregon State University. Retrieved 2022, from https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/graduate_projects/5d86p6213.

Gray, D. R. (2013). The influence of forest composition and climate on outbreak characteristics of the spruce budworm in Eastern Canada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 43(12), 1181–1195.

Meehan, T.D., G.S. LeBaron, K. Dale, A. Krump, N.L. Michel, and C.B. Wilsey. (2020). Abundance trends of birds wintering in the USA and Canada, from Audubon Christmas Bird Counts, 1966-2019, version 3.0. National Audubon Society, New York, New York, USA.

Powers, L. V., M. Pokras, K. Rio, C. Viverette, and L. Goodrich. (1994). Hematology and occurrence of hemoparasites in migrating sharp-shinned hawks (Accipiter striatus) during fall migration. Journal of Raptor Research, 28(3), 178-185.

Rosenberg, K.V., A.M. Dokter, P.J. Blancher, J.R. Sauer, A.C. Smith, P.A. Smith, J.C. Stanton, A. Panjabi, L. Helft, M. Parr, and P.P. Marra. (2019). Decline of the North American avifauna. Science, 366(6461), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw1313

Saito, E. K., Sileo, L., Green, D. E., Meteyer, C. U., McLaughlin, G. S., Converse, K. A., & Docherty, D. E. (2007). Raptor mortality due to West Nile virus in the United States, 2002. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 43(2), 206–213. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-43.2.206

Vidaña, B., Busquets, N., Napp, S., Pérez-Ramírez, E., Jiménez-Clavero, M. Á., & Johnson, N. (2020). The role of birds of prey in West Nile virus epidemiology. Vaccines, 8(3), 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8030550

Viverette, C. B., Struve, S., Bildstein, K. L., & Goodrich, L. J. (1996). Decreases in migrating sharp-shinned hawks (Accipiter striatus) at traditional raptor-migration watch sites in eastern North America. The Auk, 113(1), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/4088933

Partners in Flight, Vanishing Habitats. https://partnersinflight.org/vanishing-habitats/

Learn more about this species natural history at All About Birds or at Hawk Mountain’s website.